Mercaptans, also known as thiols, are a class of sulfur-containing organic compounds that play a significant yet troublesome role in the oil and gas industry. These compounds are naturally occurring impurities in crude oil, natural gas, and various hydrocarbon streams. While they serve practical purposes, such as odorants added to natural gas for safety detection, their presence in raw resources poses challenges related to safety, environmental compliance, and operational efficiency. This article delves into the chemical nature of mercaptans, their adverse effects on oil and gas processing, and the various methods employed to remove or mitigate them.

What Are Mercaptans?

Mercaptans are organosulfur molecules with the general formula R-SH, where “R” represents a hydrocarbon chain (alkyl or aryl group) and “SH” is the thiol functional group. They are essentially the sulfur analogs of alcohols, where the oxygen atom in an alcohol (R-OH) is replaced by sulfur. Common examples include methanethiol (CH₃SH), ethanethiol (C₂H₅SH), and longer-chain variants like butyl mercaptan. These compounds are found in all fractions of hydrocarbons, from light gases like methane to heavier oils, and their concentration can vary widely depending on the source of the crude or gas. The defining characteristic of mercaptans is their pungent, foul odor, often described as resembling rotten eggs, garlic, or cabbage. This odor is detectable at extremely low concentrations, sometimes as low as parts per billion, making them effective as warning agents but problematic in industrial settings. Mercaptans are weakly acidic due to the sulfur atom’s ability to stabilize the negative charge in their conjugate base, though their acidity decreases with increasing molecular weight of the R group. They are volatile, toxic, and can form as metabolic byproducts in living organisms or as impurities in fossil fuels.

How Mercaptans Affect Oil and Gas

The presence of mercaptans in oil and gas streams introduces several complications that impact safety, infrastructure, product quality, and economics. Primarily, their toxicity poses health risks to workers, including headaches, nausea, respiratory issues, and more severe effects like ataxia or chronic cough at higher exposures. Environmentally, uncontrolled releases can lead to air pollution and ecological harm. One of the most significant issues is corrosion. Mercaptans are highly corrosive to metals, accelerating degradation in pipelines, storage tanks, and processing equipment. This corrosion arises from their acidic nature and ability to form sulfur-based acids that attack steel and other alloys, leading to leaks, failures, and costly repairs. In refineries, mercaptans can poison catalysts used in processes like catalytic reforming or hydrocracking, deactivating them and necessitating frequent replacements, which inflate maintenance expenses.

Methods for Removing Mercaptans from Oil and Gas

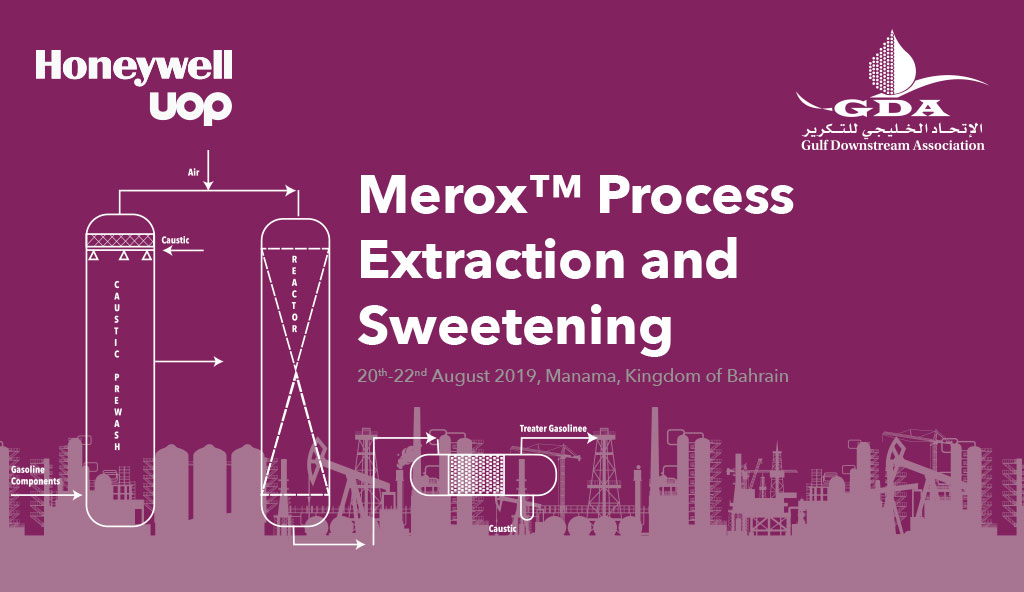

Removing mercaptans, a process often called “sweetening,” is essential to mitigate their effects. Several techniques are employed, varying by stream type (gas vs. liquid hydrocarbons), mercaptan concentration, and economic factors. These methods generally involve chemical reaction, extraction, or adsorption to convert, extract, or neutralize the compounds.Chemical Scavenging

One of the most straightforward and widely used approaches is chemical scavenging, where specialized chemicals react with mercaptans to form non-volatile, non-odorous, and non-corrosive products. Common scavengers include triazine-based compounds, which are effective for natural gas sweetening. Non-triazine options target specific mercaptans and are refinery-safe. This method is cost-effective for low to moderate concentrations and can be applied in upstream operations, though it may generate spent chemicals requiring disposal.Caustic Extraction and the Merox Process

For liquid streams like LPG or gasoline, the Merox (Mercaptan Oxidation) process is a proprietary technology that extracts and oxidizes mercaptans. It involves treating the hydrocarbon with a caustic soda (NaOH) solution to extract mercaptans as mercaptides (RS⁻ Na⁺), followed by air oxidation in the presence of a catalyst to convert them into disulfides (RSSR), which are less harmful and remain in the product or are separated. Solutizers like potassium isobutyrate enhance extraction of higher mercaptans. This process is cheaper than hydrotreating and suitable for refineries, though it doesn’t reduce total sulfur content.

Hydrodesulfurization (HDS)

For deeper sulfur removal, hydrodesulfurization uses hydrogen gas under high pressure and temperature with catalysts (e.g., cobalt-molybdenum) to convert mercaptans and other sulfur compounds into H₂S, which is then removed. This method is more comprehensive, reducing total sulfur to meet stringent fuel specifications, but it’s capital-intensive and energy-consuming, making it ideal for downstream refining rather than upstream gas treatment.Other Techniques

Oxidation with agents like sodium hypochlorite, adsorption using metal-doped activated carbon, and ionic liquid extraction are also employed in specific cases.Comparison of Mercaptan Removal Methods

| Method | Primary Application | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Scavenging | Natural gas, low concentrations | Chemical reaction to non-odorous products | Simple, low capital cost | Consumable chemicals, disposal issues |

| Merox Process | LPG, gasoline, jet fuel | Caustic extraction + catalytic oxidation to disulfides | Regenerable caustic, cost-effective | Does not reduce total sulfur |

| Hydrodesulfurization (HDS) | Crude oil fractions, deep desulfurization | Hydrogen + catalyst → H₂S removal | Deep sulfur removal, meets strict specs | High capital/energy cost |

| Adsorption | Gas streams, polishing | Physical/chemical capture on solids | Effective for trace levels | Regeneration or replacement needed |